In this lecture, I’ll describe algorithms to find the shortest cycle in a surface map that is topologically interesting. I’ll specifically consider two different definitions of “interesting”:

The input to our algorithms is a surface map \(\Sigma\) with positively weighted edges.1 I will assume throughout this presentation that there is a unique shortest path between any pair of vertices; this assumption can be enforced with standard perturbation schemes. Crucially, we will treat the underlying graph of \(\Sigma\) as a continuous topologically space; any edge with weight \(\ell\) is isometric to the interval \([0,\ell]\) on the real line. Thus, we can reasonably consider shortest paths between points that lie in the interior of edges.

It is unfortunately common for papers on surface-map algorithms to use the word “cycle” in two different senses. For topologists, a cycle is the continuous image of the circle \(S^1\), but for graph theorists, a cycle is a closed walk with no repeated vertices. That is, graph theorists assume that cycles are simple (or injective), but topologists do not. Fortunately for us, shortest nontrivial cycles are the same for both tribes.

Lemma: The shortest noncontractible (or nonseparating) closed walk in a positively edge-weighted surface map is a simple cycle.

3-Path Condition (Carsten Thomassen): Let \(x\) and \(y\) be two points (either at vertices or in edge interiors) in a surface map \(\Sigma\), and let \(\alpha, \beta, \gamma\) be paths in \(\Sigma\) from \(x\) to \(y\). If the cycles \(\alpha\cdot\textsf{rev}(\beta)\) and \(\beta\cdot\textsf{rev}(\gamma)\) are contractible (resp. separating), then the cycle \(\alpha\cdot\textsf{rev}(\gamma)\) is also contractible (resp. separating).

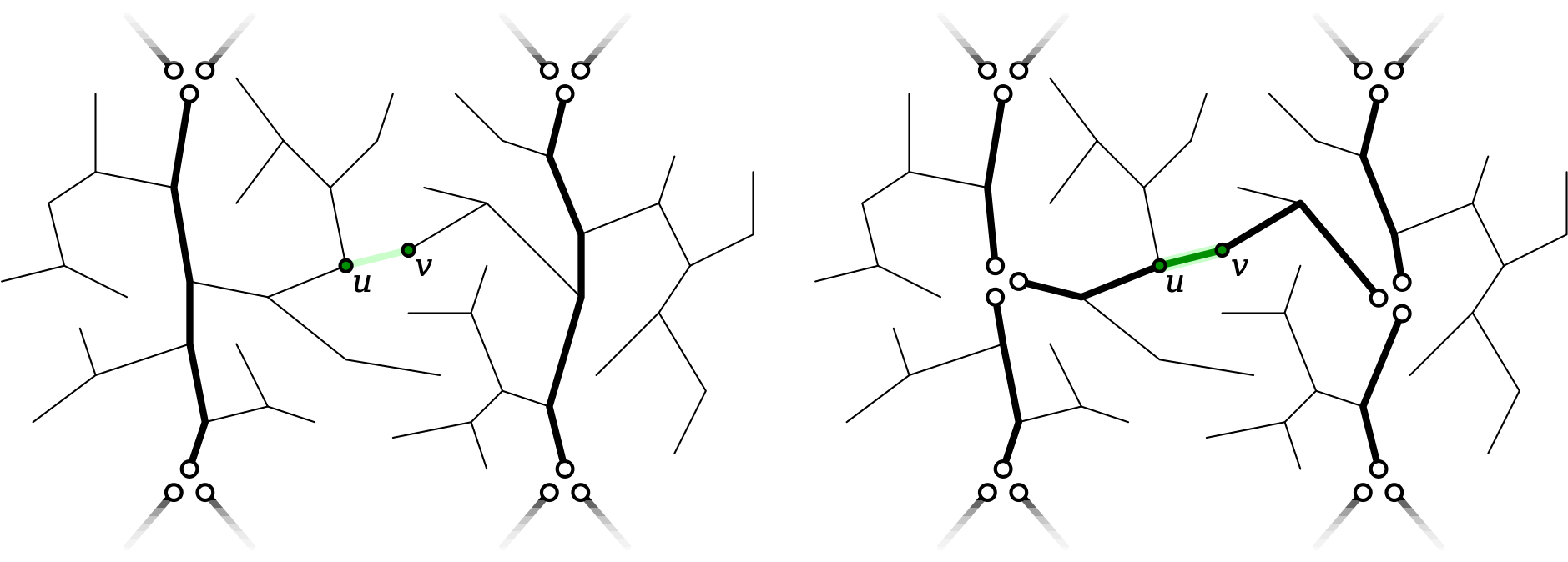

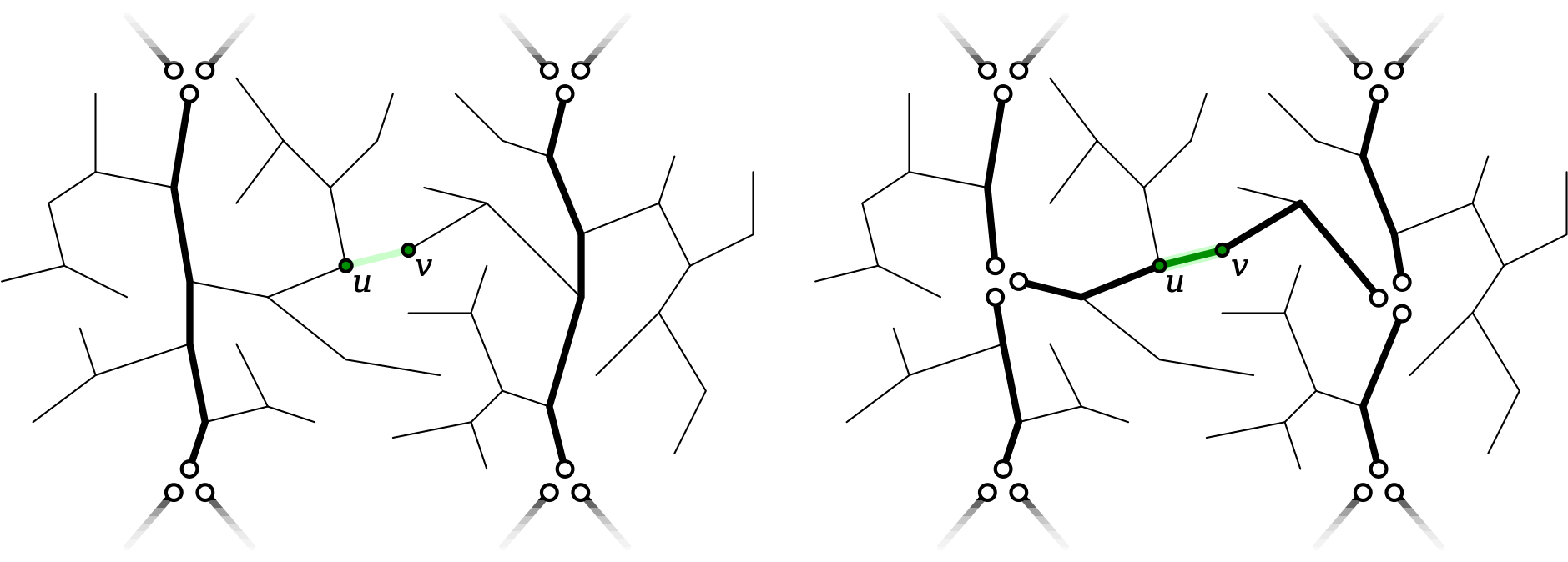

Antipodality Condition (Carsten Thomassen): Let \(\sigma\) be the shortest noncontractible (resp. nonseparating) cycle in a surface map \(\Sigma\). Any pair of antipodal points partition \(\sigma\) into two equal-length shortest paths.

Crossing Condition: Any shortest path crosses the shortest noncontractible (resp. nonseparating) cycle at most once.

Thomassen’s 3-path condition implies the following algorithm to find the shortest noncontractible cycle \(\sigma\). The antipodality condition implies that \(\sigma\) must consist of a shortest path from a vertex \(x\) to another vertex \(y\), the edge \(yz\), and the shortest path from \(z\) back to \(x\). (Uniqueness of vertex-to-vertex shortest paths implies that the antipodal point \(\bar{x}\) lies in the interior of the edge \(yz\).) There are only \(O(n^2)\) loops of this form. We compute the distance between every pair of vertices in \(O(n^2\log n)\) time by running Dijkstra’s algorithm \(n\) times, after which we can compute the length of each candidate cycle in \(O(1)\) time. Finally, for each candidate loop \(\gamma\), we test whether \(\gamma\) is contractible in \(O(n)\) time, using Dehn’s algorithm. Finally, we return the shortest candidate cycle that is noncontractible.

Theorem [Thomassen]: Given any edge-weighted surface map \(\Sigma\) with complexity \(n\), we can compute the shortest noncontractible cycle in \(\Sigma\) in \(O(n^3)\) time.

In fact, Dehn’s algorithm is overkill for testing the contractibility of simple cycles. Instead we can rely on the classical lemma:

Lemma [David Epstein2]: A nontrivial simple cycle \(\sigma\) on any surface \(\mathcal{S}\) is contractible if and only if \(\mathcal{S}\setminus \sigma\) is disconnected and at least one component is an open disk.

We can test whether a simple cycle \(\sigma\) is the boundary of a disk as follows. First, we perform a whatever-first search in the dual map \(\Sigma^*\) to determine whether the sliced map \(\Sigma \mathbin{\backslash\!\!\backslash} \sigma\) (or alternatively, the contracted map \(\Sigma / \sigma\)) is connected. If \(\Sigma \mathbin{\backslash\!\!\backslash} \sigma\) is connected, then \(\sigma\) is noncontractible. Otherwise, we compute the Euler characteristics and orientability of both components in \(O(n)\) time. If either component is orientable with genus \(1\), that component is a disk and \(\sigma\) is contractible; otherwise, \(\sigma\) is non-contractible.

We can find the shortest nonseparating cycle in the same time bound, using a slightly simpler algorithm. A given simple cycle \(\sigma\) is non-separating if and only if \(\Sigma \mathbin{\backslash\!\!\backslash} \sigma\) is connected; we can test this condition in \(O(n)\) time using whatever-first search in the dual map \(\Sigma^*\). Otherwise, the algorithm is the same.

Theorem [Thomassen]: Given any edge-weighted surface map \(\Sigma\) with complexity \(n\), we can compute the shortest nonseparating cycle in \(\Sigma\) in \(O(n^3)\) time.

Build a tree-cotree decomposition \((T,L,C)\) where \(T\) is a shortest-path tree, in \(O(n\log n)\) time, using Dijkstra’s algorithm.

Let \(X^*\) be the dual cut graph \((C\cup L)^*\). A fundamental loop \(\textsf{loop}(x,yz)\) is separating if and only if \((yz)^*\) is a bridge of \(X^*\), and contractible if and only if at least one component of \(X^*\setminus (yz)^*\) is a tree.

We can classify every edge of \(X^*\) as hair, bridge, or neither in \(O(n)\) time. So we can find shortest noncontractible and nonseparating loops based at \(x\) in \(O(n\log n)\) time.

Try all basepoints \(\implies O(n^2\log n)\) time.

The high-level approach of this algorithm is due to Sariel Har-Peled and me, but we used a much more complicated algorithm to find shortest interesting loops, which interleaves Dijkstra steps and brute-force traversal of the dual map. Replacing Dijkstra’s algorithm with a linear-time shortest-path algorithm reduces the overall running time to \(O(n^2)\).

This is the fastest algorithm known for arbitrary genus. However, Martin Kutz proved that for any constant genus \(g\), it is possible to computer shortest nontrivial cycles in only \(O(n\log n)\) time, by a reduction to the planar minimum-cut problem (or more properly, to the dual problem of finding the shortest generating cycle in an annulus). The running time of Kutz’s algorithm depends exponentially on the genus. Later work by Sergio Cabello and Erin Chambers reduced the dependence on \(g\) to a small polynomial.

We can significantly improve Thomassen’s algorithm using a generalization of either of the multiple-source shortest path algorithms that we saw earlier for planar maps.

[The rest of this section is only an outline.]

Grove decomposition of the dual cut graph \(T\cup L\) into \(O(g)\) trees, each with a central cut path. Each pivot requires \(O(g)\) dynamic-forest operations, and thus takes \(O(g\log n)\) amortised time. Each dart pivots into the shortest path tree \(T\) at most \(O(g)\) times. Total time is \(O(g^2 n\log n)\), assuming generic edge weights. This can be improved to \(O(gn\log n)\) time with more careful data structures and analysis.

Consider the subgraph \(X^* = C^*\cup L^* \cup \{e^*\}\) of the dual map \(\Sigma^*\). The induced embedding of \(X^*\) has exactly two faces, each containing (the faces of \(\Sigma^*\) dual to vertices of) one component of \(T \setminus e\). Let \(Y^*\) be the boundary subgraph comprised of the non-isthmus edges of \(X^*\). This boundary subgraph can be decomposed into at most \(g+1\) simple non-crossing cycles. (Recall the the definition of the genus \(G\) is the maximum number of disjoint cycles whose deletion does not disconnect the surface.) Each of these cycles crosses \(B\) at most twice. Thus, either \(X^*\) does not cross \(B\) at all, or \(X^*\) splits \(B\) into at most \(2g+2\) intervals, which alternate between vertices of \(U\) and vertices of \(W\). \(\qquad\square\)

Precompute homology annotations (via a system of cocycles) once at the start. Compute shortest-path trees \(T_i\) and \(T_j\) in \(O(n\log n)\) time. Compute homology signatures of all shortest paths from \(s_i\) and \(s_k\) in \(O(gn)\) time. Dart \({u{\to}v}\) is properly shared by \(T_i\) and \(T_k\) if it satisfies the following conditions:

The second condition holds if and only if these two shortest paths define a separating arc from \(s_i\) through \(u\) to \(s_k\).

Finding and contracting all properly shared darts takes \(O(gn)\) time. Each vertex has \(O(g\deg(v))\) interesting sources, so the total size of all maps at each level of recursion is \(O(gn)\). The total preprocessing time is \(O(gn\log n + g^2 n)\); the query time is still \(O(\log n)\). It’s unclear whether \(O(gn\log n)\) time can be achieved with this approach.

Lemma [Cabello Mohar]: The shortest nonseparating cycle in any surface map \(\Sigma\) crosses at least one cycle in a greedy system of cycles for \(\Sigma\) exactly once.

Lemma: For any cycle \(\gamma\), the shortest cycle that crosses \(\gamma\) exactly once can be computed in \(O(\bar{g}^2 n\log n)\) time.

Now let \(\sigma\) be the shortest cycle in \(\Sigma\) that crosses \(\gamma\) once. This cycle appears in \(\Sigma’\) as a shortest path from \(v^-\) to \(v^+\) for some vertex \(v\) of \(\Sigma\). We can compute all such shortest paths in \(O(\bar{g}^2 n\log n)\) time using either MSSP algorithm, using either \(\gamma^+\) or \(\gamma^\pm\) as the “outer” face. \(\qquad\square\)

Theorem: The shortest nonseparating cycle in a surface map with Euler genus \(\bar{g}\) and complexity \(n\) can be computed in \(O(\bar{g}^3 n\log n)\) time.

For each cycle \(\gamma_i\), we compute the shortest cycle in \(\Sigma\) that crosses \(\gamma_i\) exactly once, in \(O(\bar{g}n\log n)\) time, by running a multiple-source shortest-path algorithm in \(\Sigma \mathbin{\backslash\!\!\backslash} \gamma_i\). The shortest of these \(\bar{g}\) cycles is the shortest nonseparating cycle. \(\qquad\square\)

This one is a bit more complicated.

Lemma: Every noncontractible cycle in any surface map \(\Sigma\) crosses any cut graph of \(\Sigma\) at least once.

The following lemma distills a more complex argument of Cabello, Chambers, and Erickson. [[[Take this with a grain of salt until I wrote down a complete proof.]]]

Lemma: Let \(\sigma\) be the shortest noncontractible cycle in some surface map \(\Sigma\). Let \((T,L,C)\) be a tree-cotree decomposition of \(\Sigma\) where \(T\) is a shortest path tree and \(C\) is a maximum spanning tree. Let \(\mathcal{C}\) denote the corresponding system of cycles.

Lemma: Let \(\sigma\) be the shortest noncontractible cycle in some surface map \(\Sigma’\) with genus \(0\) and at least two boundaries. Let \(\pi\) be the shortest path between any two boundaries of \(\Sigma’\). Either (a) \(\sigma\) crosses \(\pi\) exactly once, or (b) \(\sigma\) does not cross \(\pi\) and \(\sigma\) is the shortest noncontractible cycle in \(\Sigma’ {\backslash\!\!\backslash} \pi\).

Theorem: The shortest noncontractible cycle in a surface map with Euler genus \(\bar{g}\) and complexity \(n\) can be computed in \(O(\bar{g}^3 n\log n)\).

First, for each cycle \(\gamma_i\), we compute the shortest cycle in \(\Sigma\) that crosses \(\gamma_i\) exactly once, in \(O(\bar{g}^2 n\log n)\) time, by running a multiple-source shortest-path algorithm in \(\Sigma \mathbin{\backslash\!\!\backslash} \gamma_i\). The shortest of these \(\bar{g}\) cycles is the shortest nonseparating cycle. Thus, if the shortest noncontractible cycle is nonseparating, then the shortest of these \(\bar{g}\) cycles is the shortest noncontractible cycle. Otherwise, we need to compute the shortest noncontractible cycle in the sliced surface \(\Sigma’ = \Sigma \mathbin{\backslash\!\!\backslash} \mathcal{C}\).

The surface \(\Sigma’\) has genus 0 and \(b\) boundary cycles, for some \(1\le b\le \bar{g}\). If \(b=1\), then \(\Sigma’\) is a disk, so every cycle in \(\Sigma’\) is contractible. Otherwise, we compute a shortest path \(\pi\) between any two boundary cycles, compute the shortest cycle \(\sigma^\times\) in \(\Sigma’\) that crosses \(\pi\) exactly once via multiple-source shortest paths, and recursively search \(\Sigma’ \mathbin{\backslash\!\!\backslash} \pi\). The algorithm halts after computing \(b-1\) cycles; the shortest of these is the shortest noncontractible cycle in \(\Sigma’\).

Altogether the algorithm runs multiple-source shortest paths \(\bar{g} + b = O(\bar{g})\) times, each on a surface map with complexity \(O(n)\) and genus less than \(\bar{g}\). So the overall running time is \(O(\bar{g}^3 n\log n)\), as claimed. \(\qquad\square\)

Sergio Cabello, Erin W. Chambers, and Jeff Erickson. Multiple-source shortest paths in embedded graphs. SIAM J. Comput. 42(4):1542–1571, 2013. arXiv:1202.0314.

Sergio Cabello and Bojan Mohar. Finding shortest non-separating and non-contractible cycles for topologically embedded graphs. Discrete Comput. Geom. 37(2):213–235, 2007.

David B. A. Epstein. Curves on 2-manifolds and isotopies. Acta Math. 115:83–107, 1966.

Jeff Erickson. Shortest non-trivial cycles in directed surface graphs. Proc. 27th Ann. Symp. Comput. Geom., 236–243, 2011.

Jeff Erickson, Emily Kyle Fox, and Luvsandondov Lkhamsuren. Holiest minimum-cost paths and flows in surface graphs. Proc. 50th Ann. ACM Symp. Theory Comput., 1319–1332, 2018. arXiv:1804.01045.

Jeff Erickson and Sariel Har-Peled. Optimally cutting a surface into a disk. Discrete Comput. Geom. 31(1):37–59, 2004. arXiv:cs/0207004.

Emily Kyle Fox. Shortest non-trivial cycles in directed and undirected surface graphs. Proc. 24th Ann. ACM-SIAM Symp. Discrete Algorithms, 352–364, 2013. arXiv:1111.6990.

Martin Kutz. Computing shortest non-trivial cycles on orientable surfaces of bounded genus in almost linear time. Proc. 22nd Ann. Symp. Comput. Geom., 430–438, 2006. arXiv:cs/0512064.

Carsten Thomassen. Embeddings of graphs with no short noncontractible cycles. J. Comb. Theory Ser. B 48(2):155–177, 1990.

With more effort, these algorithms can be generalized to directed surface maps with asymmetrically weighted darts.↩︎

David Epstein-with-one-p is a curly-haired English mathematician who was born in South Africa. David Eppstein-with-two-p’s is a curly-haired American mathematician (and computer scientist) who was born in England. It’s a minor miracle that they have never been coauthors.↩︎